It’s light when I leave work, daffodils are peaking, and heartbreaker Monty Don and his heartbreaking box blight are back on our screens. It’s spring and I feel simultaneous joy and panic. The reasons for rejoicing are obvious, but the fear comes from a sense that I’m somehow never ready for this point and should have devoted more time in hibernation to planning my flawless growing season to come.

I have at least spent the winter looking at gardening books, and, as the gardening year begins in earnest, now seems like a good time to share some of my favourites. These aren’t the ‘best’ books or even those that relate to my favourite gardens or aspects of gardening – I’ve avoided any designers’ or garden monographs and a lot of beautiful books with fascinating content - but they are compelling as overall packages and feel somehow significant to me. Some are books I was conscious of from long before it would have occurred to me to buy a gardening book of my own.

The scope of my choices is necessarily limited, spanning a period from the late twentieth century to now, and I feel like I’ve fallen into a bit of a trap in that many authors and contributors are from privileged backgrounds. Garden writing, like many creative fields, has been dominated by the upper echelons and it's especially easy to see why that's the case with this particular discipline. Great garden writing has often sprung from the writer having a great garden of their own and even more so than with say, fine art or music this has tended to necessitate a lot of space, time and money. This is in contrast to the activity of gardening itself, which has historically traversed the class spectrum; I’d recommend George McKay’s Radical Gardening: Politics, Rebellion & Idealism in the Garden (2011) as an antidote to some of the more parterre-heavy tomes.

Garden Design by David Hicks (1982)

I picked Garden Design up in Oxfam, attracted by the graphic appeal of its cover. It really is the strangest book. David Nightingale Hicks, well-connected interior decorator to the glitterati in the second half of the twentieth century, did some pretty sick stuff, his signature being to combine geometric patterns in extraordinarily dynamic colour combinations with neoclassical and Colefax and Fowler-type English country house elements. The orange labyrinth tiles at London’s Warren Street tube station always remind me of his work, and I feel like if you’ve seen these, the pretty white and green tromp l’oeil trellises at Sloane Square station and - returning to the Victoria line - the icon of the demolished triumphal arch at Euston, you’ll be fairly well on your way to understanding his approach. (The Warren Street design is actually by Crosby/Fletcher/Forbes; see Victoria Line Tiles).

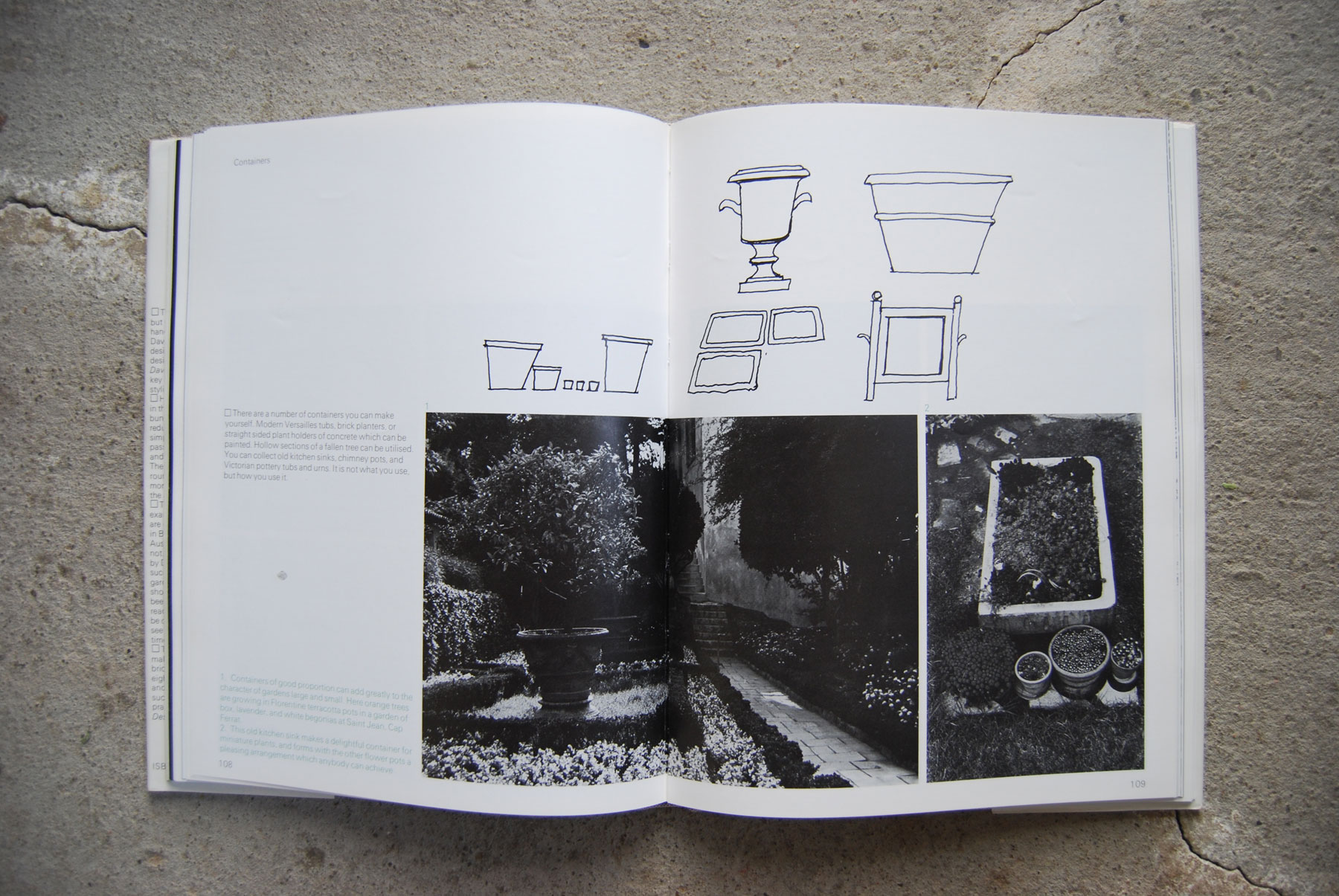

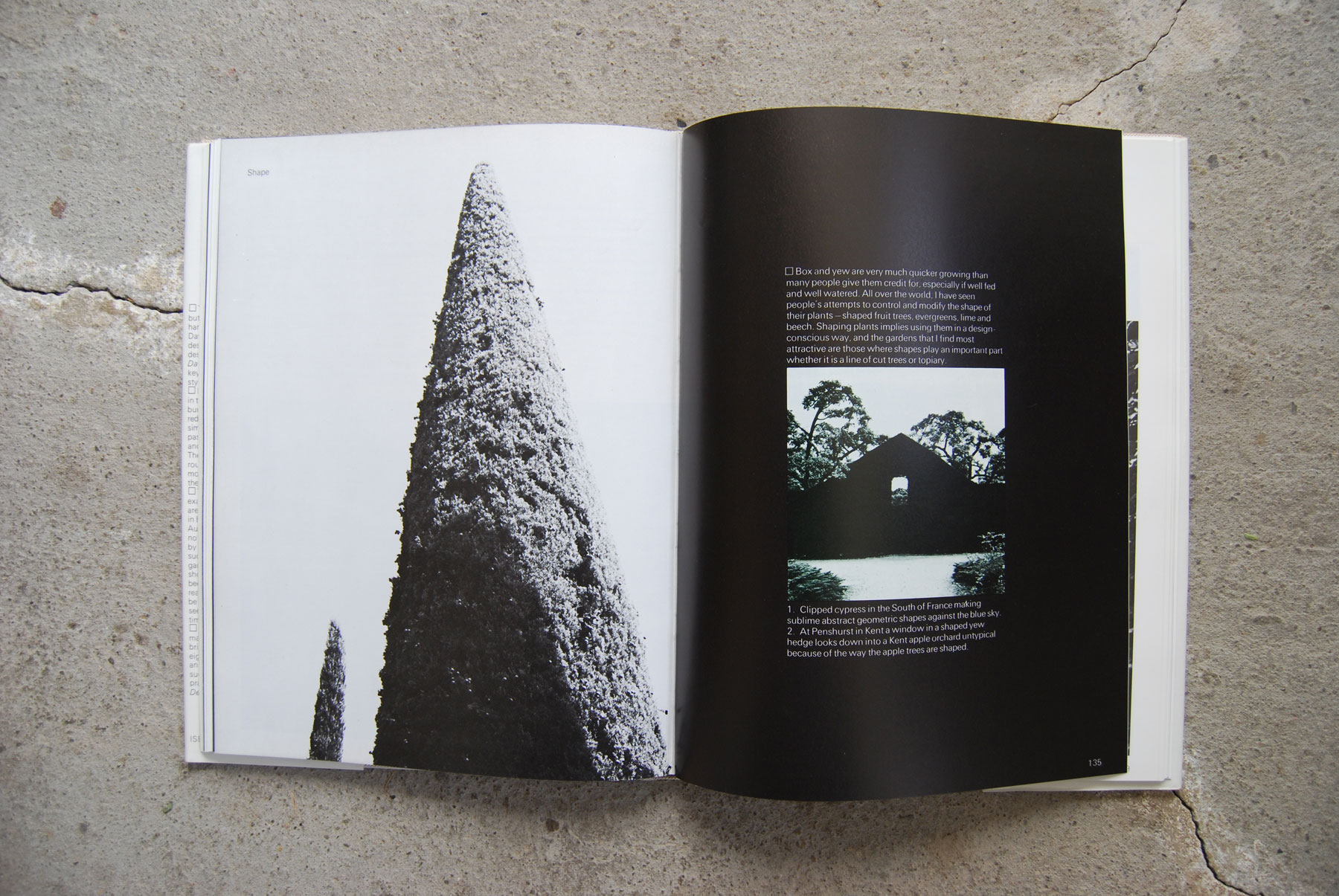

It’s the sheer audacity of Garden Design – ostensibly a ‘practical handbook’ - that’s amazing. To begin with, the largely black and white photographs are underexposed to the point of being almost illegible. This would be infuriating if you were using it as a reference tool, but it also imbues them with a mysterious if unintentionally abstract beauty. Images like that of the Dowager Lady Camoys’ yew shapes take on a surrealist quality, reminiscent of the photography of Paul Nash. Nicholas Jenkins’ book design is very stylish but again the elegant lightness of the type makes it less legible than one might hope (and in 2017 it’s difficult to not to read the chic square device inserted at the beginning of every paragraph as a frustratingly unsupported Emoji).

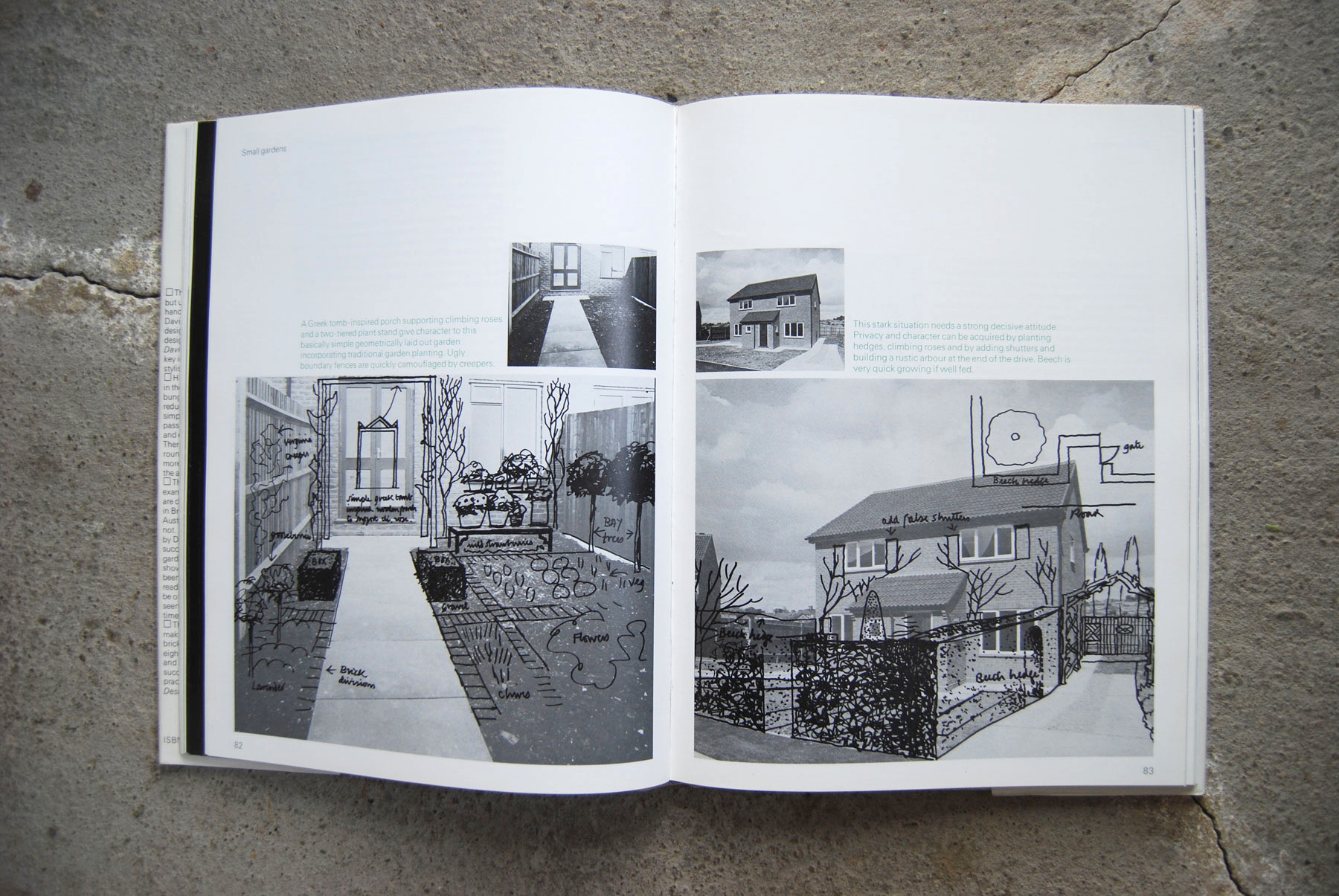

Hicks also employs spreads of sketches produced especially for this book, of the type I immediately recognised from those angsty all-nighters before my illustration degree deadlines, where you realise your submission needs more ‘research’ to beef it up and so frantically fill sketchbook pages with tenuously relevant shite off the top of your head. Reproduced handwritten captions like ‘NB. Sunday Times supplement says cobbles cheaper that (sic) brick for paving’ support the theory that Hicks preferred not to trouble himself with unnecessarily exhaustive legwork.

The best aspect of the book, and the one I find genuinely inspiring, is the few pages Hicks devotes to doodling on images of small, blank new build estate houses, in much the same way you might absent-mindedly draw specs or dicks on people’s faces in the Metro. As Hicks says, ‘small gardens should neither be grand or pretentious’: apparently neither a ‘simple Greek tomb inspired wooden porch to support cli. rose’ added to the back of a tiny terraced house nor ‘period detail… added to the fenestration’ in the form of Gothick glazing bars on a utilitarian flat-roofed garage fall into these categories. The book was published in 1982 and this section feels in tune with the right-to-buy mania of the time, when former council tenants across the UK were celebrating their newfound homeowner status with mock Georgian replacement front doors. While I have severe reservations about the long-term effects of the policy, I can’t pretend I’m not all for the aesthetics of unbridled grandiosity. Certainly I have more time for Hicks’ approach than that of, say, the Duke of Gloucester who, in a foreword to John Prizeman’s Houses of Britain: The Outside View (2007) implores the proletariat to stay in their exterior decoration lane, writing ‘After all nobody’s fooled if you put a Rolls Royce bonnet on a Mini’. To be fair, Hicks’ Greek tomb porch might not be wholly convincing as a Greek tomb, but it is a right laugh.

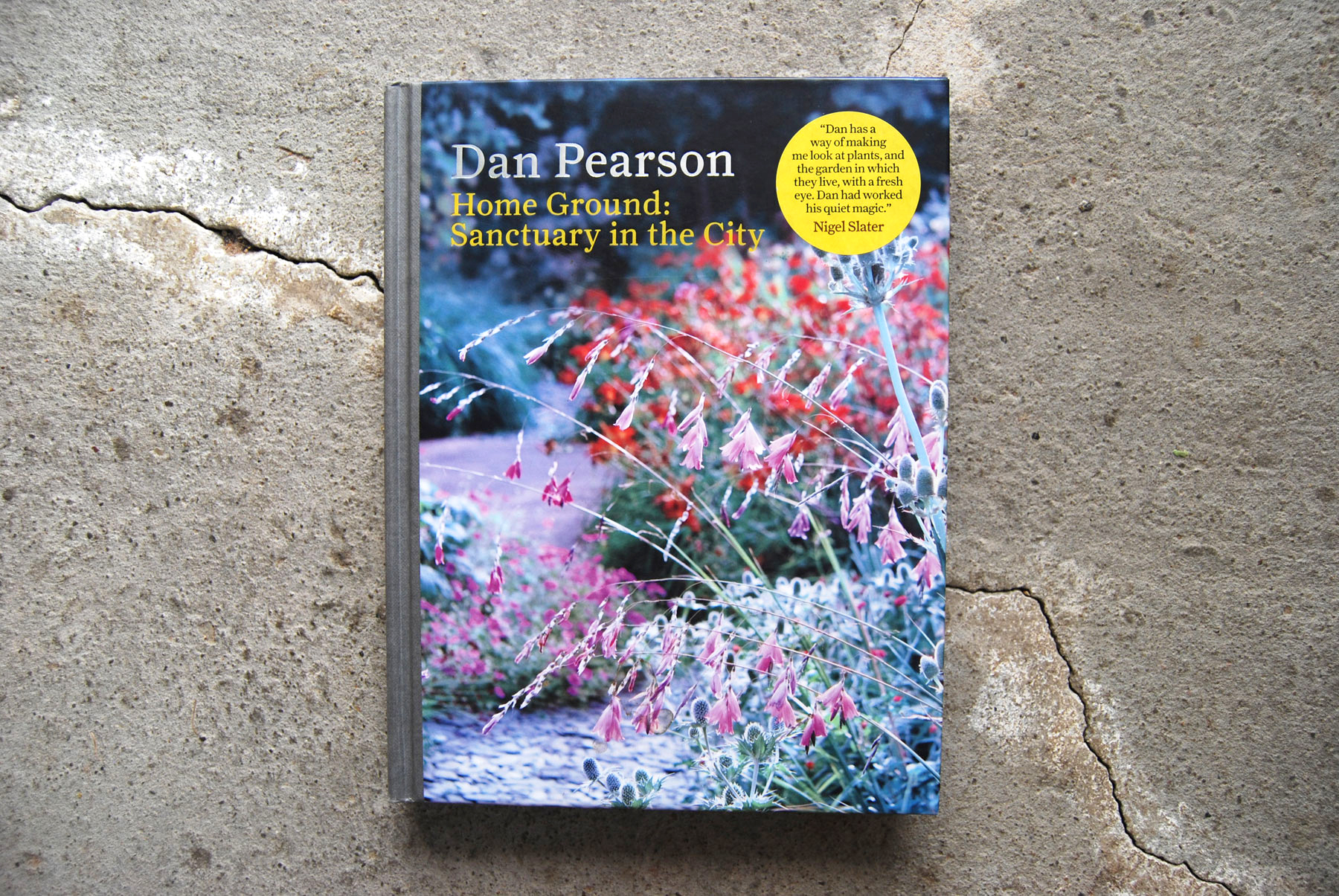

Home Ground: Sanctuary in the City by Dan Pearson (2011)

When I lived in Camberwell and Peckham in a series of student houses in the late noughties, Dan Pearson’s Observer Magazine columns, often based around his SE15 plot, felt like dispatches from a parallel universe. While one of the scant pleasures of the London rental market was that you often ended up in a house share with a garden of some description, at that point I had yet to decide that embracing them would be a) an acceptable use of my time and b) key to my personal brand. In those years I quietly limited my horticultural efforts to relatives’ gardens when back home for the holidays.

I did however take an open interest in the local front gardens, which were generally tiny but diverse in character, from unkempt jungles to the South Ken-aping peacocking of big, big box balls in big, big pots. I would procrastinate by telling myself I’d leave my work for half an hour to get some air, then go walking for hours - I think Croydon was the furthest I ever got before suffering an attack of conscience - in thrall to the ever-changing variations on suburban house and garden themes that unfolded. So it was frustrating that I hadn’t been able to identify Pearson’s house, until, making my way home from a party one late April early morning, senses impaired, my attention was caught by the giant Rosa banksiae 'Lutea' he’d alluded to in an article, lighting up the street.

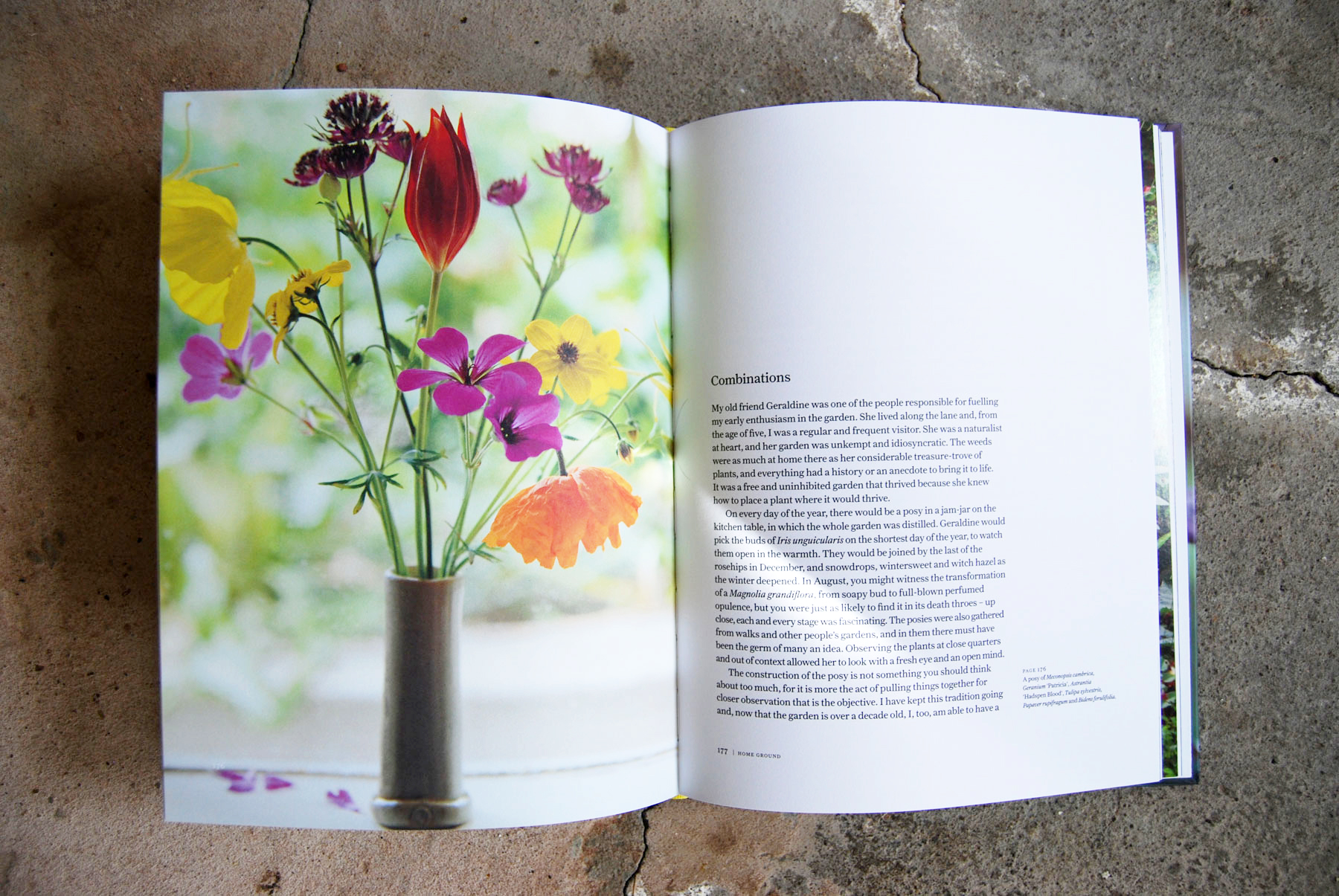

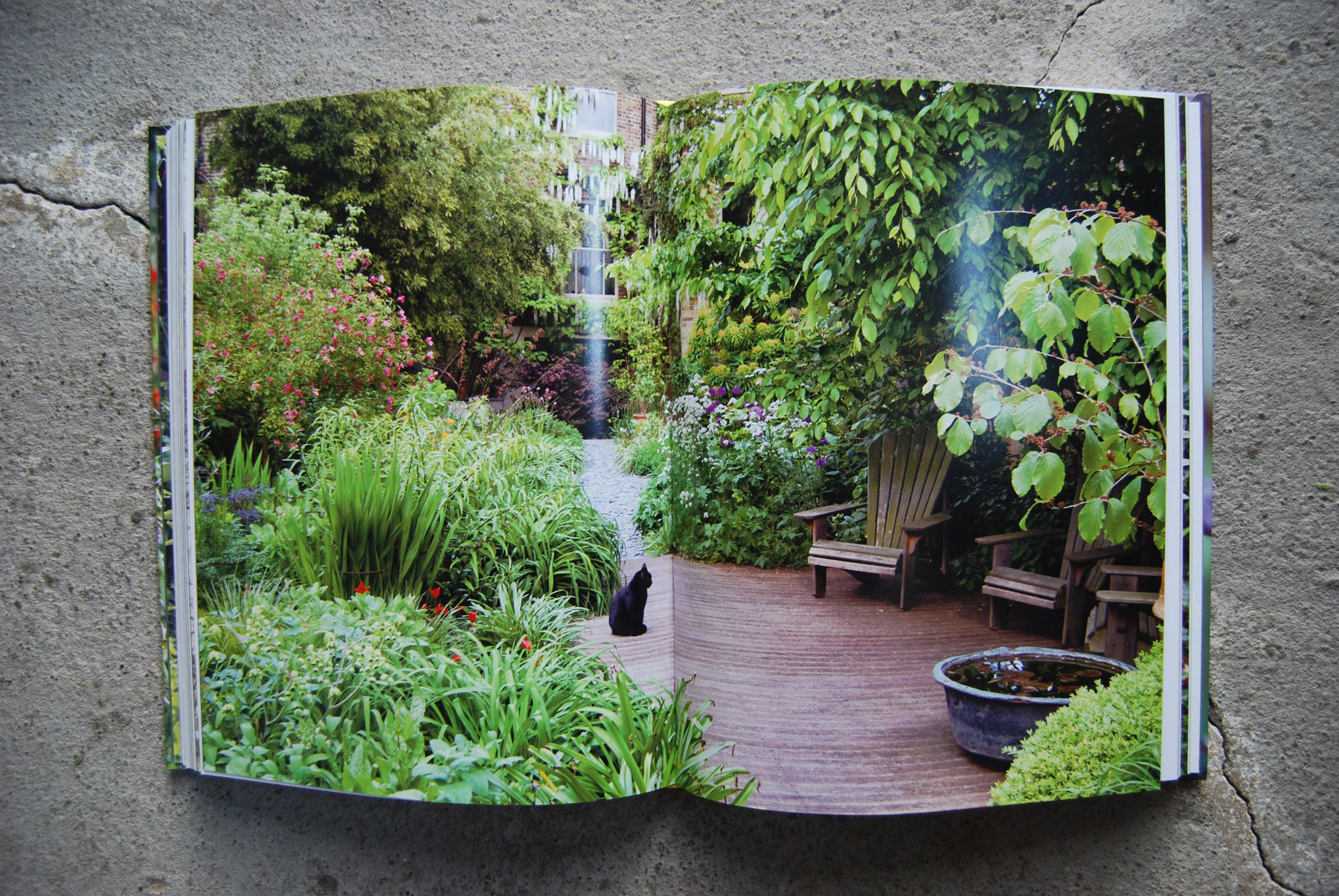

Home Ground focuses on Pearson’s Peckham garden, beginning with an account of its inception, before moving through the seasons, with short chapters focused on particular plants, aspects of maintenance and design and gardening texts. In its mixture of practical advice with personal recollections and musings it surely owes something to Christopher Lloyd, though Pearson’s approach is gentler and less categorical. As ever his writing is as effortlessly apt as his planting style and the Howard Sooley photographs are a dream, done justice by glossy spreads scattered through the book’s matt pages. There are many loving portraits of plant combinations and flowers but the image I always return to is a serene early summer view of the whole garden, layers of greenery concealing its urban surroundings and, right in the middle, a lucky black cat taking it all in.

Pearson recently launched Dig Delve, more than making up for the absence of his Sunday columns.

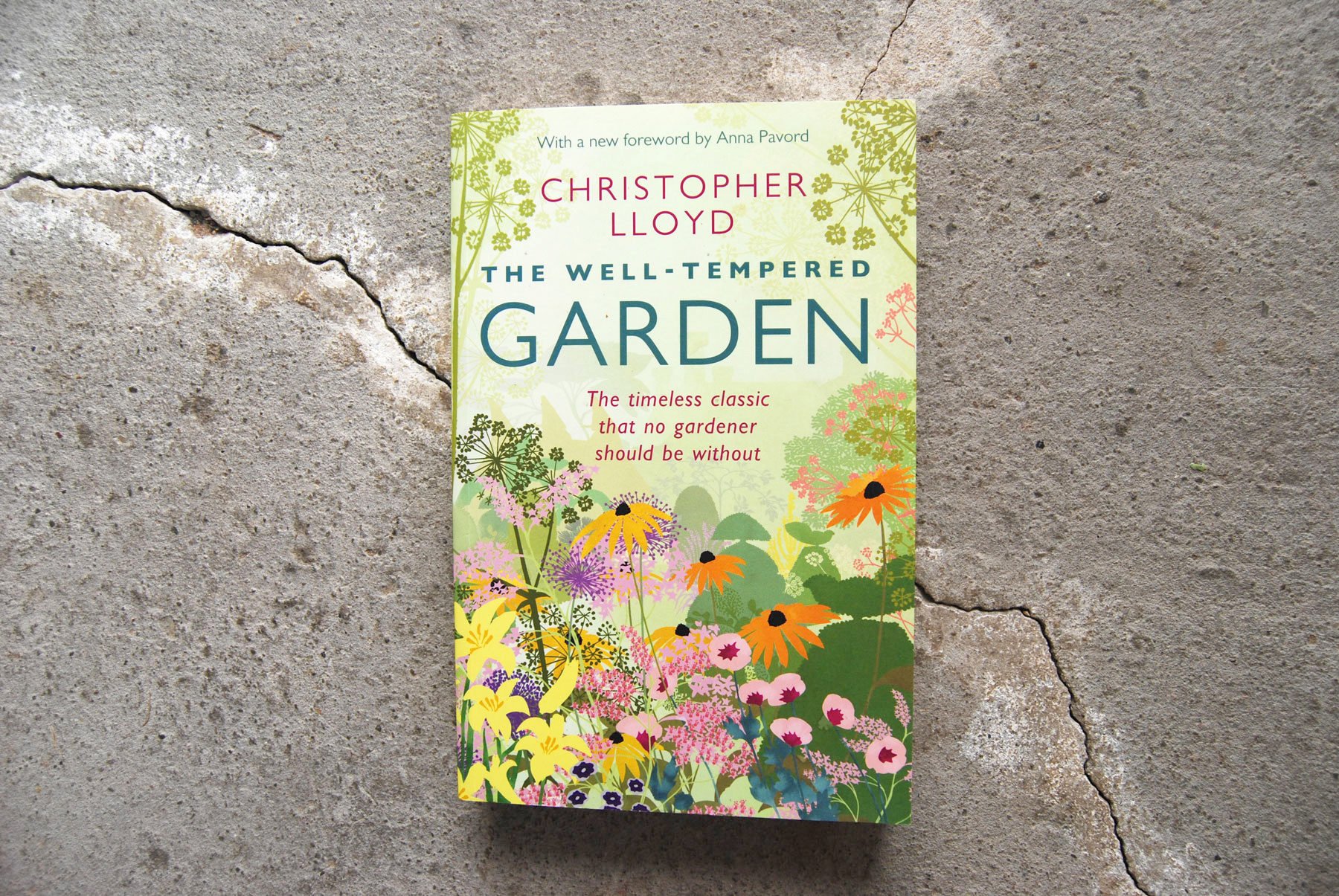

The Well-Tempered Garden by Christopher Lloyd (first published 1970)

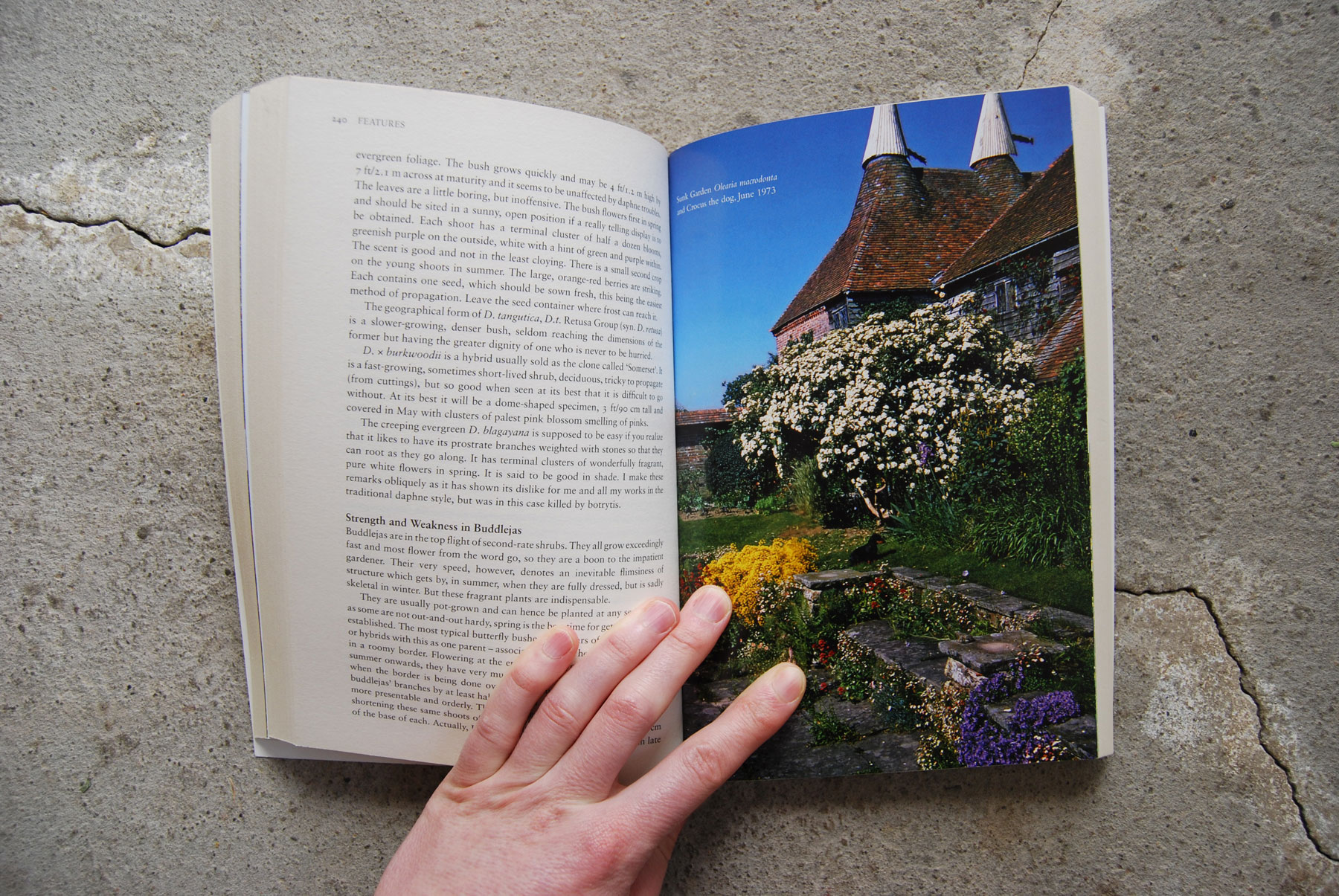

‘The timeless classic that no gardener should be without’ reads the subtitle on my edition of The Well-Tempered Garden and so it is. The late Lloyd and his Sussex garden Great Dixter, of the exuberant tropical planting, Lutyens house and ripped-out rose garden, have been so well documented that there is little for me to add, but this is truly one of those books that is both useful reference tool and deeply comforting to read a few pages of in bed.

Lloyd’s Guardian column was a feature of my childhood, like Monty Don’s that preceded Dan Pearson’s in The Observer. The Well-Tempered Garden takes the form of chapters with somewhat enigmatic headings, divided into smaller sections that manage to cover every essential area of gardening in an eminently practical way, without ever feeling textbook-like. Lloyd’s descriptions of plants are hugely evocative, and his waspish wit comes through on every page. Writing at a time when the popular gardening approach was in many respects at odds with his own (I detect some distaste for Percy Thrower), it’s clear he didn’t suffer fools gladly. The overwhelming sense though is of Lloyd’s great knowledge and joy in gardening, generously shared.

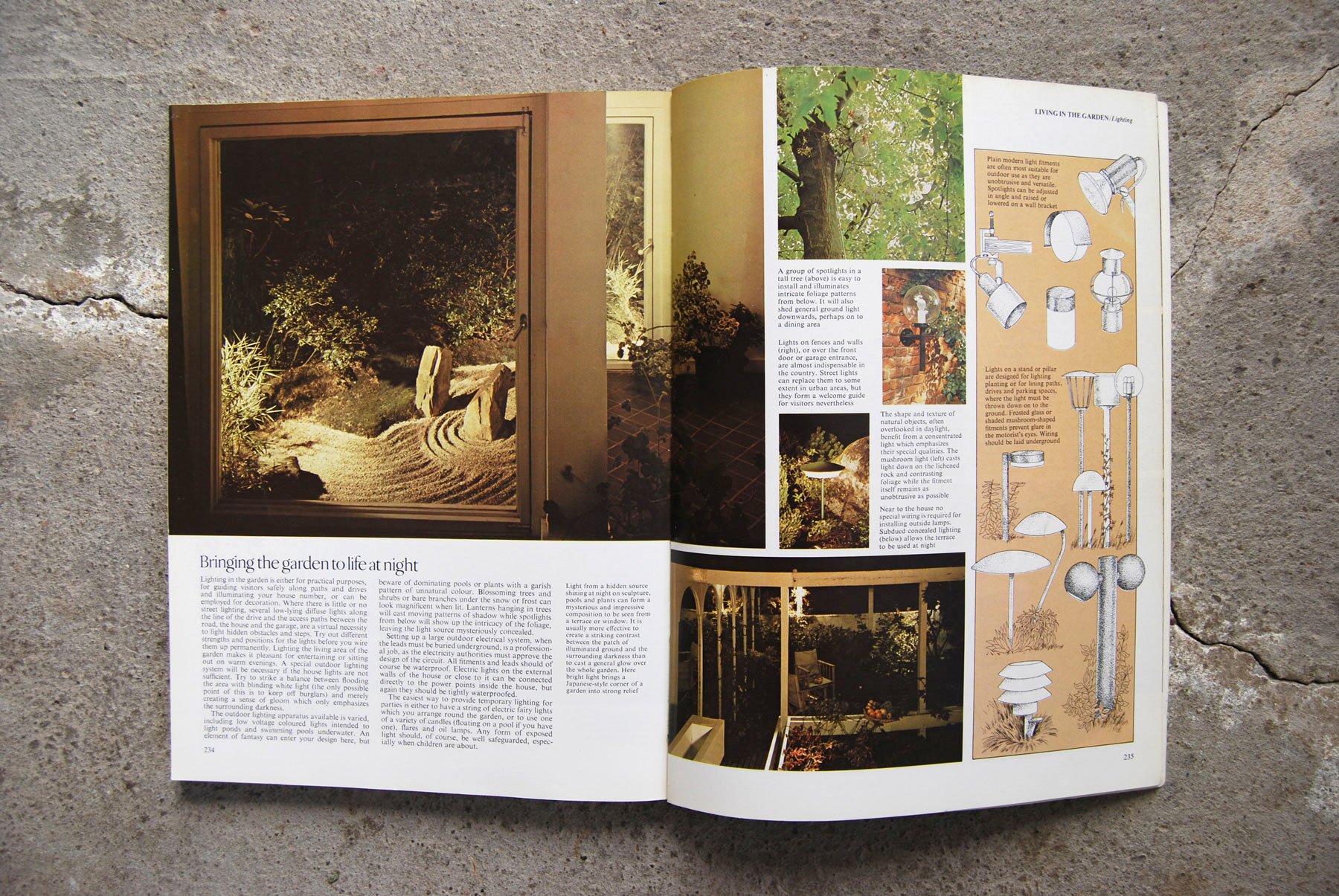

The Small Garden by John Brookes (first published 1977)

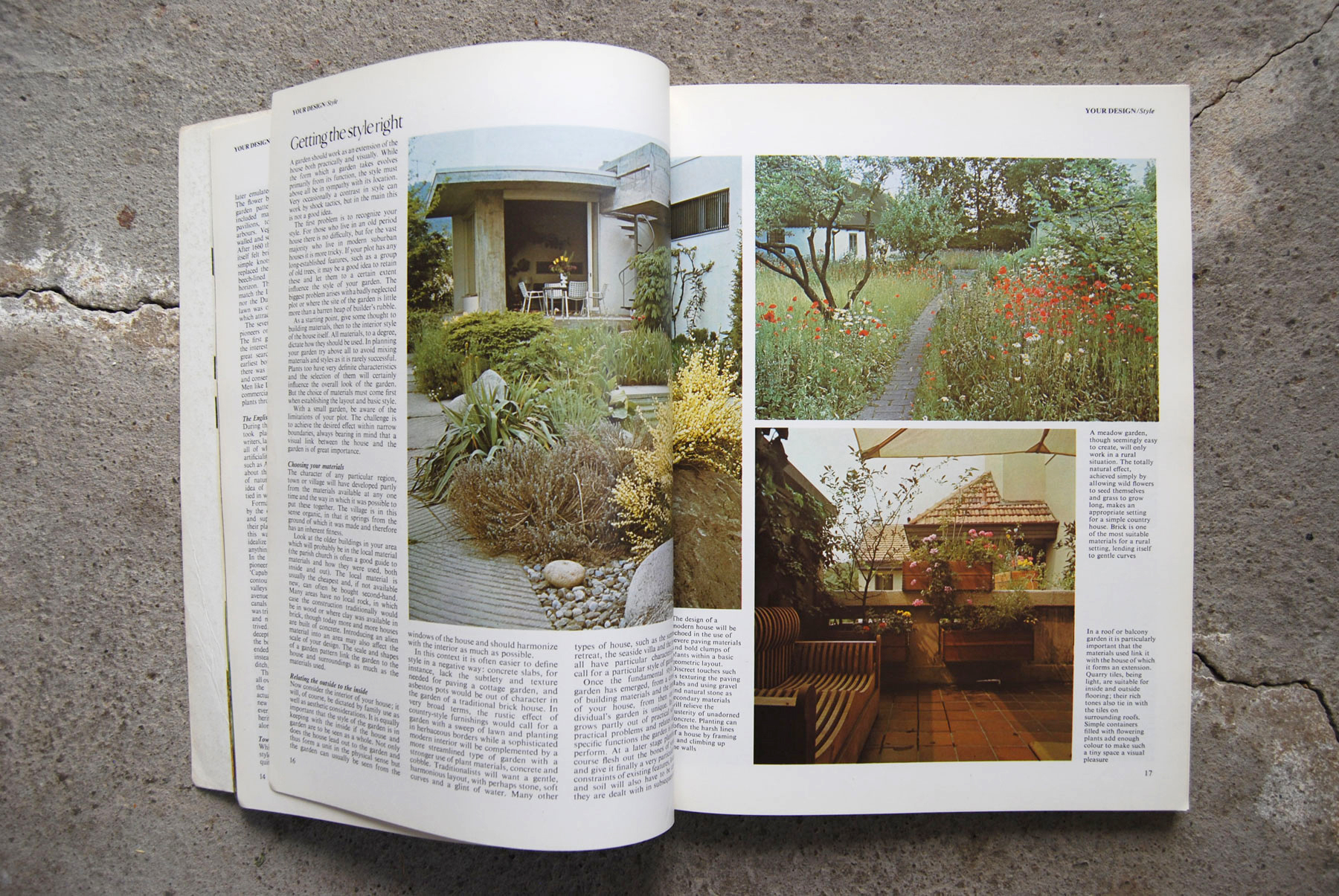

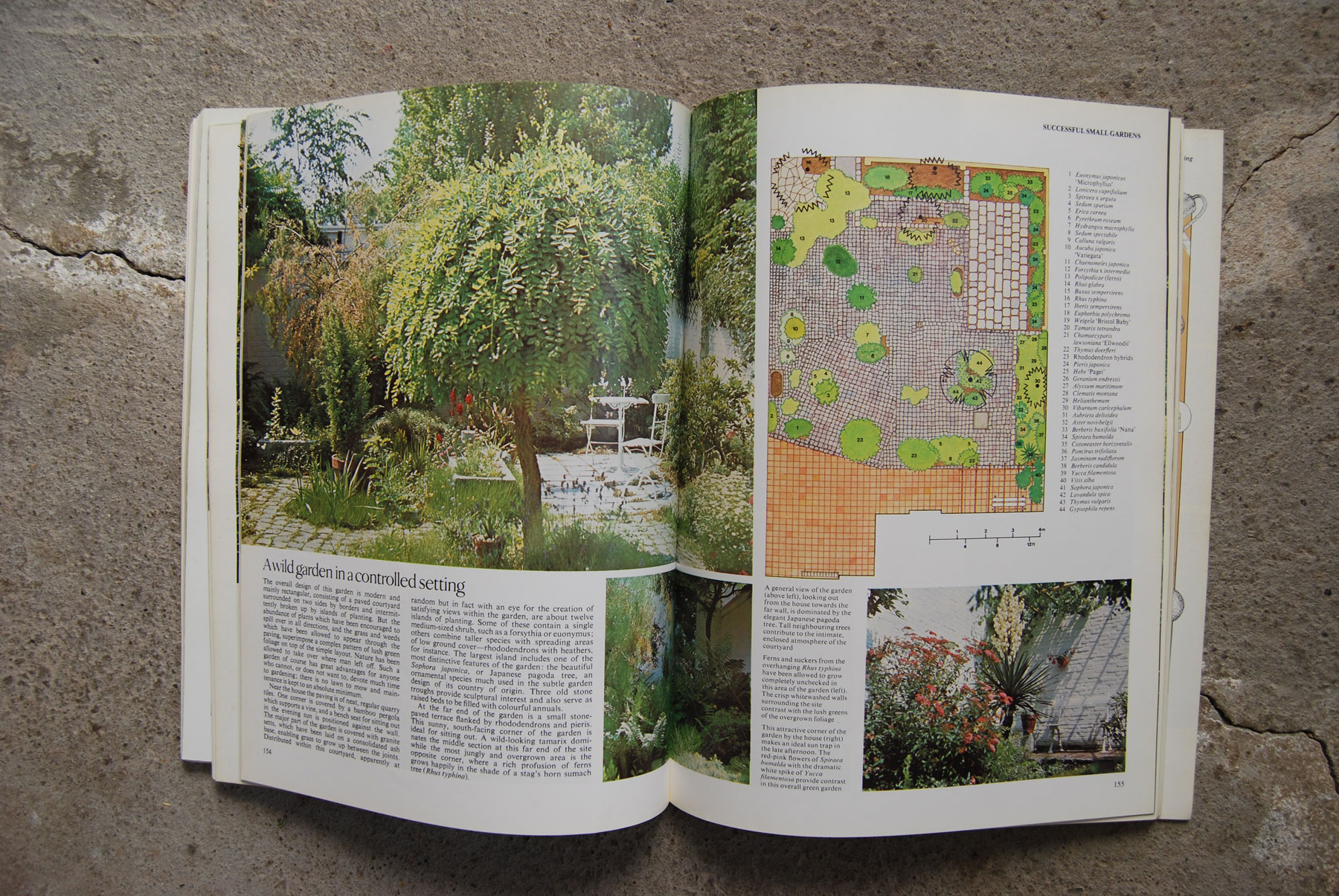

This is the only gardening book I remember my parents having when I was very wee; later on there was the Ground Force book then Monty Don’s Urban Jungle. Back then my tastes were, as is kids’ wont, conservative – I remember being enthralled by Gay Search’s TV front garden makeovers to adjoining bay-fronted Victorian terraced houses. I came across a picture of them recently and the cast concrete terracotta-effect rope edging and chimney pot-inspired planters didn’t look quite as smart as I remembered. Anyway, even while this was my beau ideal I devoured The Small Garden, whose approach is decidedly modernist, albeit at the later, cosier end of the spectrum. It feels in many ways like the garden equivalent of Terence Conran’s era-defining The House Book; on checking my copy of the latter I see Brookes himself actually contributed its ‘Outdoors’ section.

Brookes has had a distinguished career as a landscape designer and The Small Garden is full of both practical hard landscaping and design advice. There are lots of small gardens (including properly small, urban spaces) both photographed and illustrated with wonderful gouache illustrations, the only part of this period piece that now feels a little kitsch.

Growing up I only really came across spaces reminiscent of those extolled in The Small Garden in neglected municipal developments: occasional corners of shopping centres conceived as open air piazzas and not yet encased in flashy nineties glass and pink tiles; long since abandoned landscaped areas around high rise flats; concrete planters, cobbles set in cement, abstract modern sculpture with an organic feel. In a way, my visit to Gonçalo Ribeiro Telles and António Viana Barreiro’s exquisite Gulbenkian Park in Lisbon last October was the first time I’d really seen this approach live up to its potential, thanks to excellent planting, continued investment and perhaps a more concrete-friendly climate. It’s one of the most inspired gardens I’ve ever experienced and as I wandered around it The Small Garden kept popping into my head.

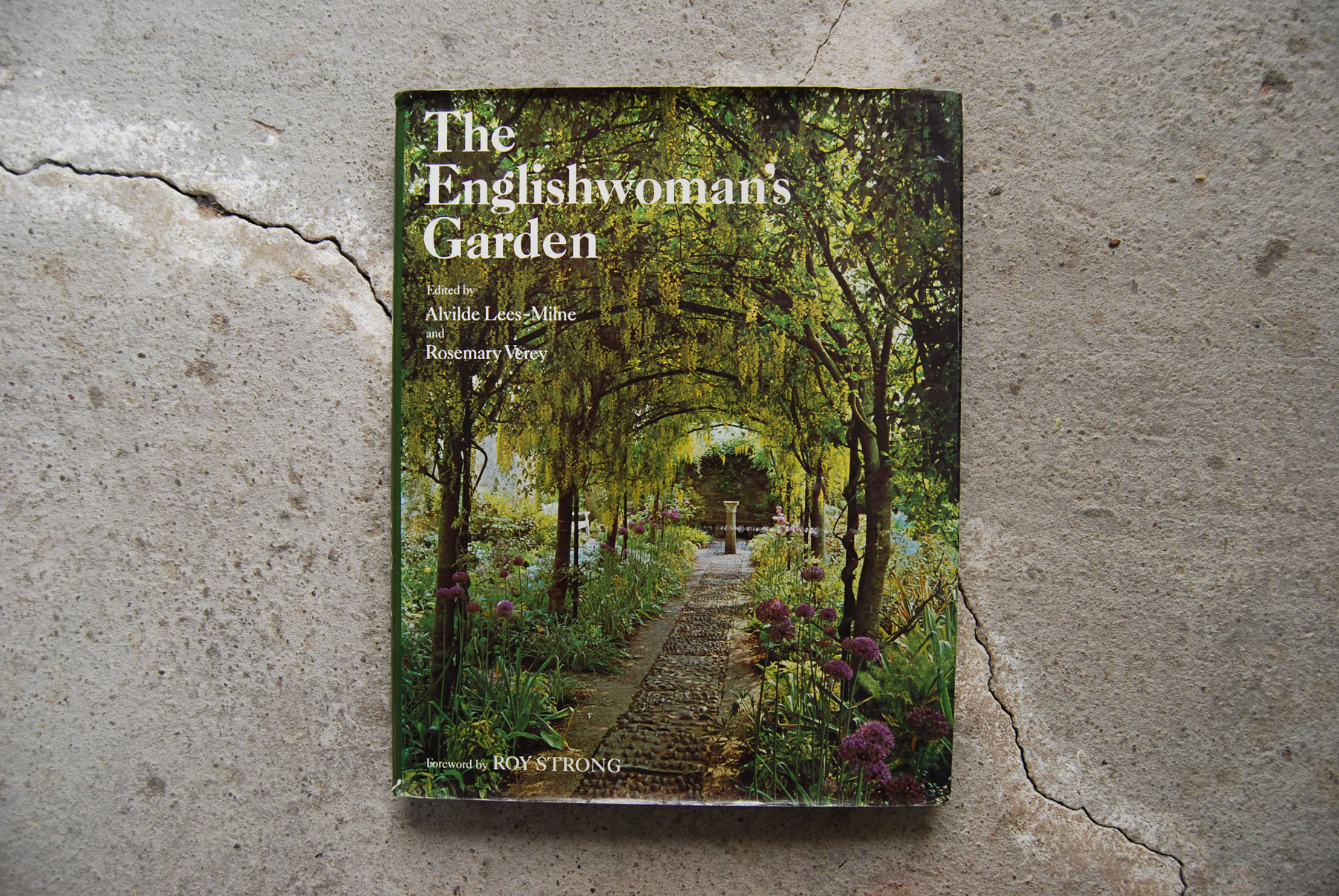

The Englishwoman's Garden edited by Alvilde Lees-Milne and Rosemary Verey (1980)

I didn’t realise The Englishwoman’s Garden was part of a loose series covering most aspects of 1980s posh style until I was a postgrad at the Royal College of Art where I discovered The Englishwoman’s Wardrobe when moonlighting as a shelf-tidier in the college library. I spent a good few minutes hiding in a bay checking out the wavy garms and the curious contexts they were shot in, all puffball sleeves worn to backdrops of antique dolls’ houses and Austrian blinds.

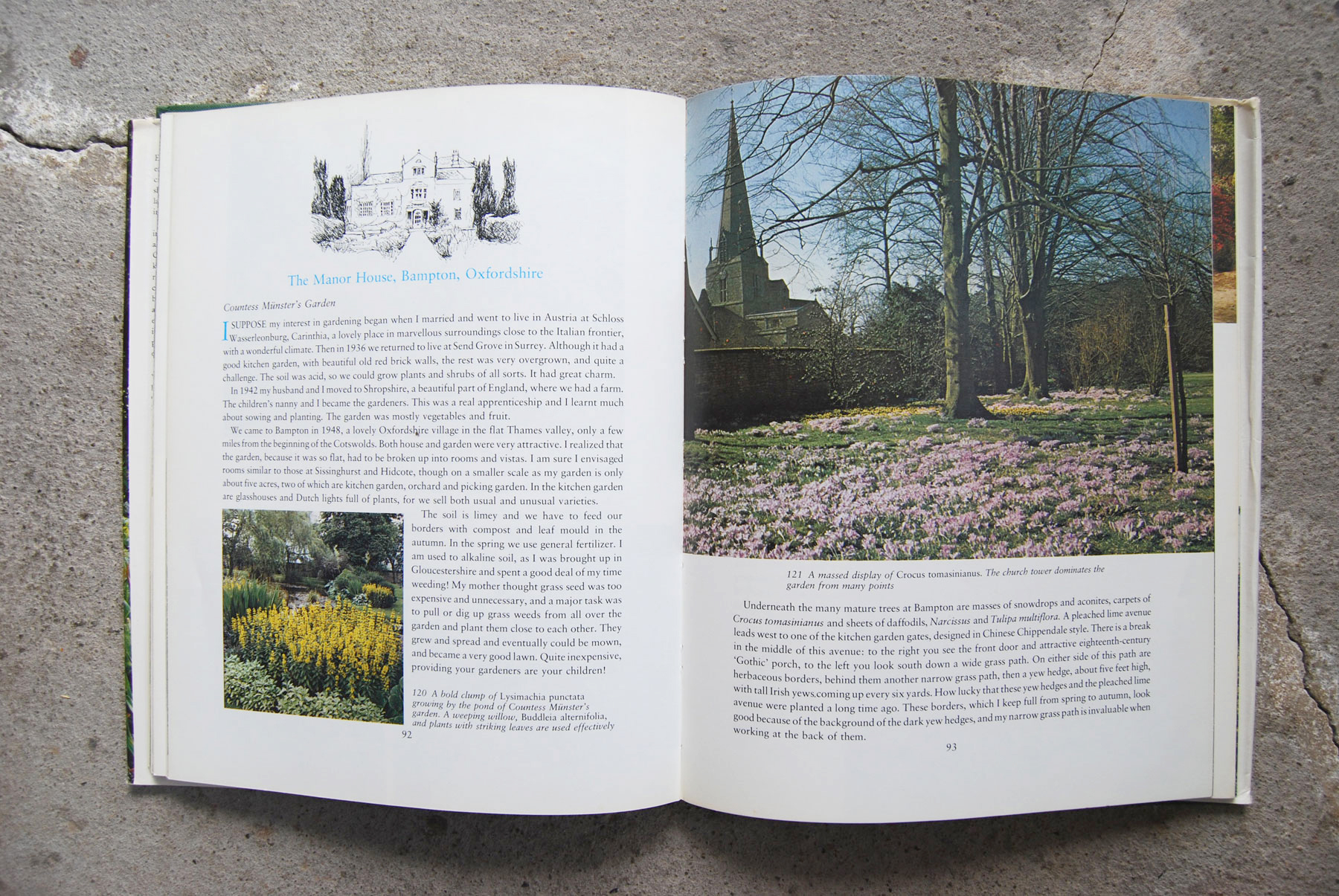

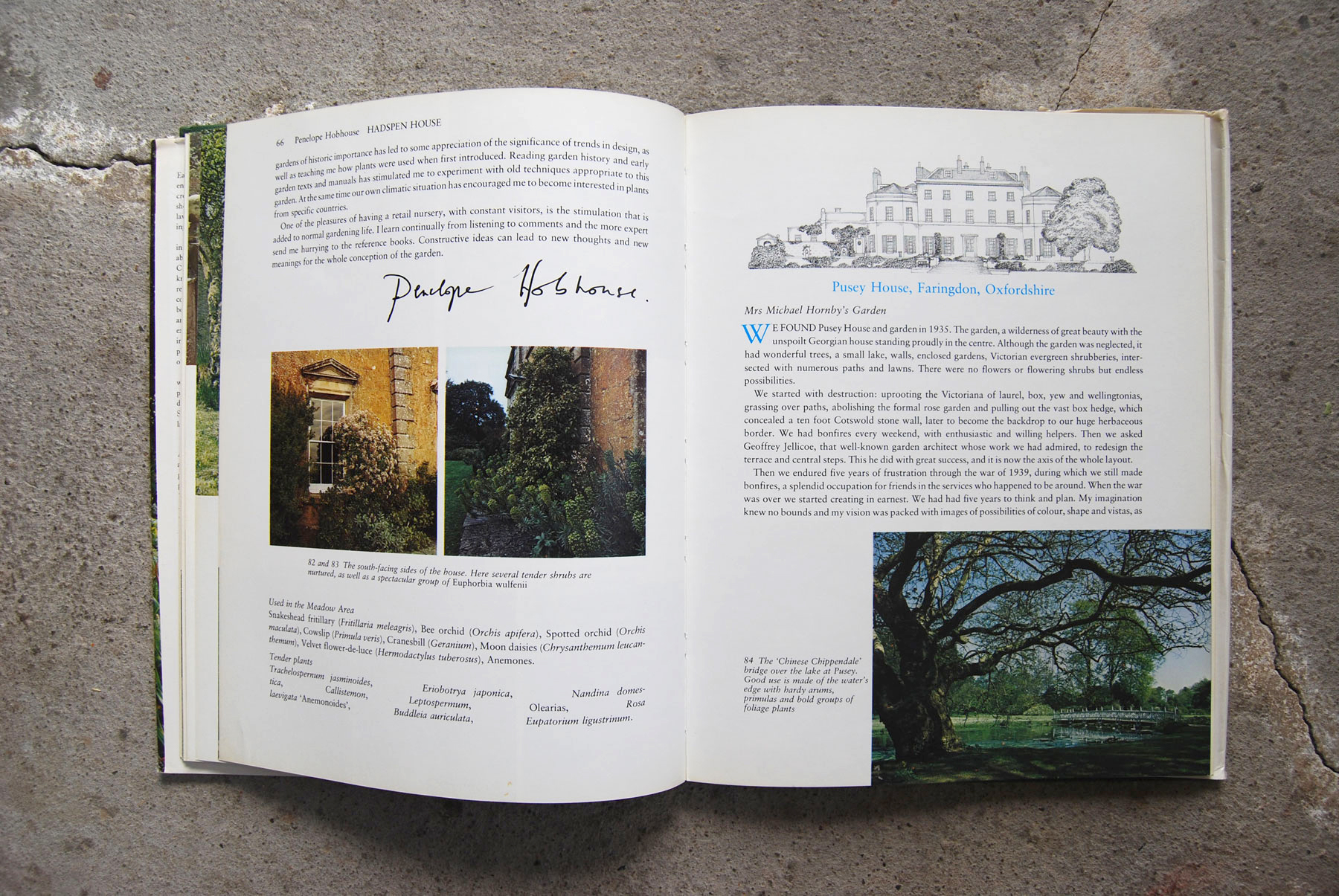

I’ve chosen The Englishwoman’s Garden over its brother The Englishman’s, partly since the women in it are less apt to drop horrifying politics than the men but also because my affection for it is longstanding, there having been a copy of it in the bedroom bookcase at my grandparents’ house. The book consists of a selection of generally upper class women describing their gardens, from the famous and grand (women and gardens) to the comparatively obscure and modest, in short essays.

In this company, it’s hard not to go full Nancy Mitford and cringe when, for example, one woman refers to her ‘leisure garden’ (although I’m certain I must be too common to understand why this phrase is actually totally acceptable). The ladies are all introduced under their husband’s names, so it’s quite strange to see living gardening legends like Penelope Hobhouse and Beth Chatto reduced to Mrs Paul and Mrs Andrew. Rosemary Verey’s own laburnum tunnel at Barnsley House – an image that you could just about get away with describing as iconic – adorns the cover. She’s a figure I’ve found increasingly intriguing since reading Roy Strong describe her as “barred from several houses” for risqué behaviour, a surprising flipside to her passion for knot gardens and neat grey perm.

It is interesting to see some famous gardens that have evolved hugely since the book was published, though the modestly sized, desaturated (a reaction to the oversaturation of previous decades?) photographs mean each garden almost fades into one romantic dream: think pinks in the cracks of York stone paving, mixed shrub borders, carpets of bulbs backed by church spires, ancient yew topiary and classical ornament. It’s all too nostalgic, not least because leafing through it I can almost feel the resolutely non-U flannelette sheets of my Nairn second home against my skin.

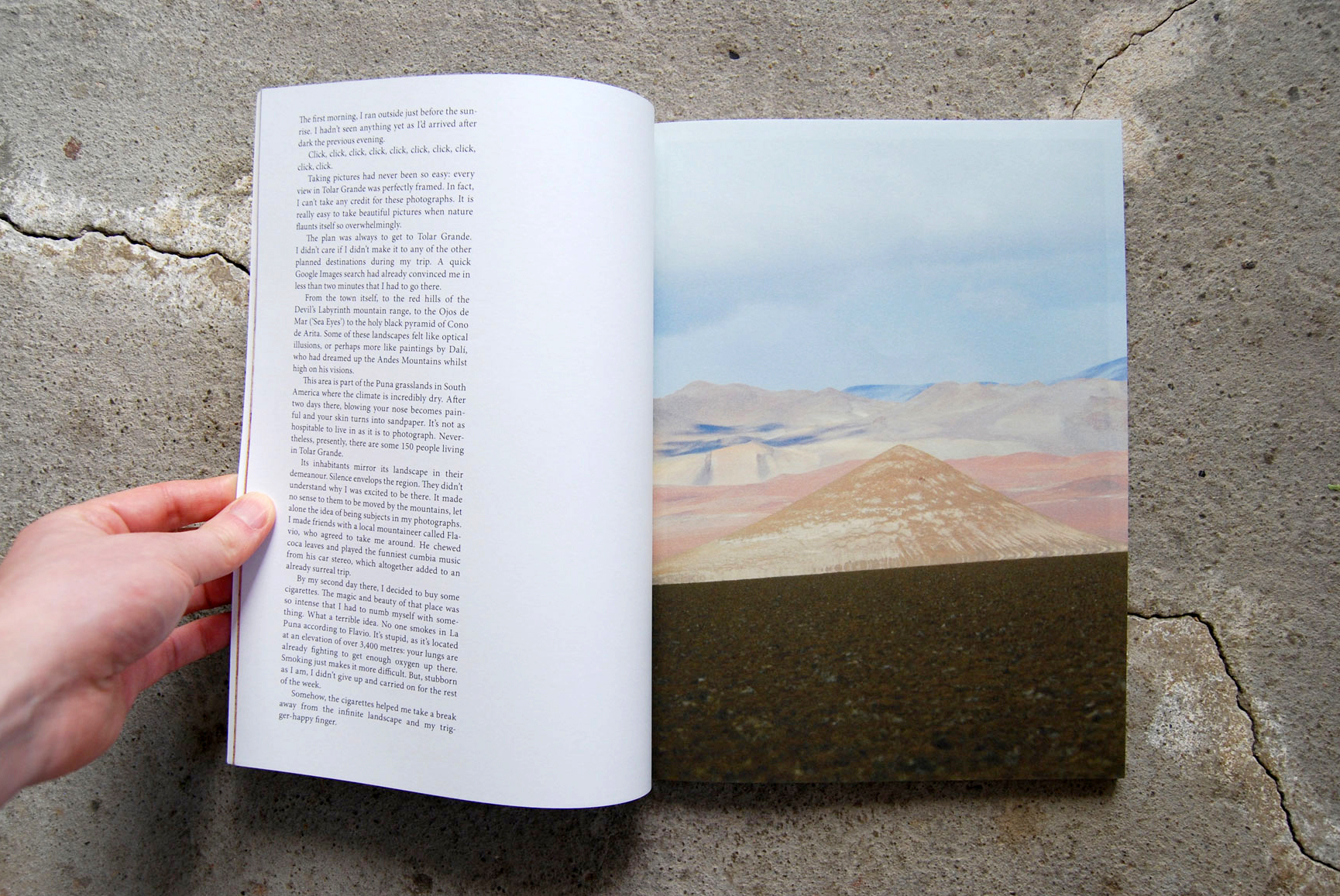

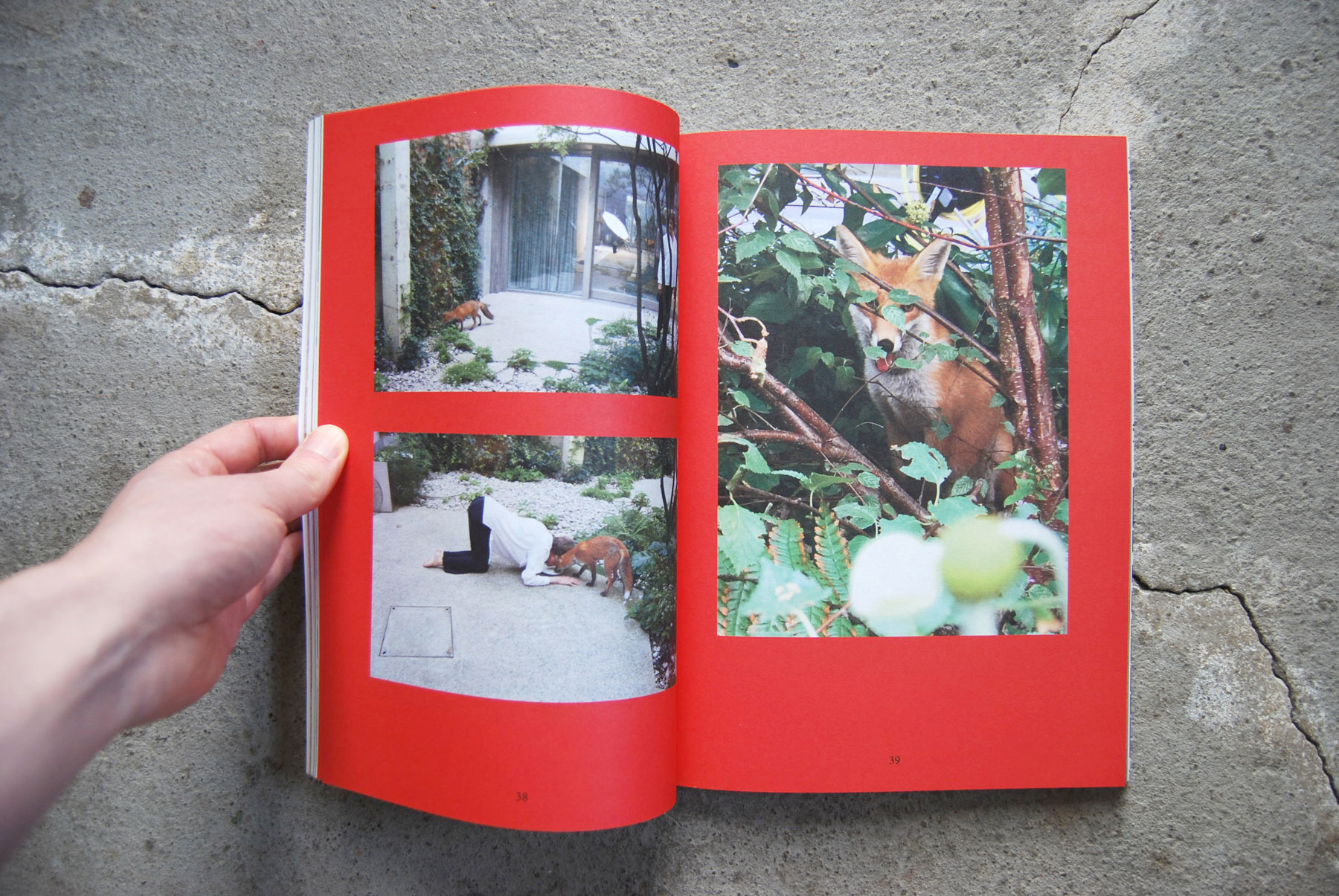

The Plant edited by Cristina Moreno (2011-)

The Plant is a magazine rather than a book, but I’m including it as the content and production values are such that you’re not going to stick it in the recycling after reading. I can’t think of The Plant without a tinge of regret, since back when it launched in 2011 and my old pal Ella Plevin ordered me a copy as a birthday present. It kept getting lost in the post, and I think she managed to get 3 copies sent out altogether before realising she’d given them the wrong house number. Naturally, I sprinted along to my neighbours’ door to try and reclaim at least one, where I was frostily informed they’d never seen it. I have my doubts, because their front garden definitely had a bit more joie de vivre about it that summer.

Anyway, the thing about The Plant is that it was one of the first publications I saw that made me think that my interest in gardening, a vaguely guilty open secret throughout my youth, was something that could legitimately relate to the rest of my life without being all-consuming. I already had a cheeky Gardens Illustrated habit (I still adore and subscribe to GI) but a magazine skewed towards the Wiltshire rectory-owning market, unironically splashing ‘Design Ideas for Follies’, wasn’t always full of relatable content for me. At the same time, attempts by gardening media to be young and relevant always seemed to be of the gimmicky sub-Diarmuid Gavin, plasma TV in a purple concrete wall or three galvanised buckets in a row variety. This kind of approach persists; I’m thinking of the likes of the 2016 Chelsea gold-medal winning Vestra Wealth garden, described as ‘ooz(ing) contemporary cool’. With its weird hyperreal London background it kind of did to me, but maybe not in the way it was intended: it felt like a postinternet artist’s damning critique of globalisation and neoliberalism.

The Plant is fresh and fun and you don’t need to have or even aspire to have a garden to enjoy it. It casually traverses art, cooking, landscapes and design and in this regard belongs to a group of publications like The Gourmand and Apartamento that approach their subjects in a way that’s both cerebral and playful (and in their happy country-hopping hammer home how utterly gutting the prospect of Brexit is). The photography is brilliant and they know how to use paper stock. As time has passed it has attracted increasingly high profile contributors (Nick Knight, Dan Pearson, Juergen Teller et al in the latest issue) but still has a warm insouciance and accessibility about it: a contributor like Luis Venegas will tell us how he ties his houseplants’ leaves together in groups to make them shine. Surely a horticultural hint as helpful as knotting your daffodil leaves after they’ve flowered, but so sweet.